Bond Strategy Update February 2016

Misallocation of Capital

The concept behind Quantitative Easing and Zero Interest Rate Policy is to encourage investors to take risks, to rekindle their ‘animal spirits’, which to many, is the driving force behind investments, and therefore, growth.

It seems that the central banks got what they wished for. Extraordinary monetary policies had pushed up the prices of commodities and spurred massive investments in their extraction, including crude oil. Since China ‘must have a bottomless appetite’, the whole exercise seemed to make sense.

Such massive investments involved substantial creation of credit, which investors were more than happy to oblige to. Recent news about financial difficulties facing commodities producers and their financiers revealed that over investment, or, misallocation of capital, might have been the case.

Over supply is everywhere, the slowdown in China is a symptom, not the cause.

The fallout includes depressed commodities prices, rising defaults (lenders and borrowers) and the resulting risk aversion that often chokes investment decisions, and if they are severe enough, could lead to recessions.

The year started with a thunderous roar of volatility. Crude oil fell below US$30 a barrel, the Chinese Yuan, both the Onshore and Offshore versions, depreciated further against the U.S. Dollar, equities retreated dramatically, and government bonds rallied despite strong competition from large corporate debt issuances.

As active managers, we at Caldwell are not adverse to volatility and uncertainty. It is in these environments that our in-depth analysis and well-thought out strategies really shine, making it easier for us to differentiate ourselves. We strive to generate Alpha – the absolute return one can get through active management of an investment portfolio, and also to better protect our clients’ capital.

The Credit Market

Years of Zero Interest Rate Policy has pushed investors out the risk curve to get them higher yields by taking on higher credit risks. Since late 2014 the credit markets have been deteriorating. Those invested in credit market instruments have seen the value of their investments shrink. The weakness was not noticeable until mid-2015, when the deterioration had already been well-entrenched.

At press time, most lesser-rated corporate credit indices were at their worst levels in over four years; that is, those who have purchased corporate debt or corporate debt-related instruments in the past four years are seeing losses in their investments. (The widening of credit spreads has raised the discount rate, for dividends or yields, from those credit and equity instruments and significantly lowered their prices.) A reversal back to the upside for these lesser-rated credit instruments seems less and less likely. 2016 could be another year of declining values in lesser-rated corporate debt instruments.

The problem is accentuated by the fact that corporate debt outstanding has doubled since 2006 but the capacity by banks and dealers to trade and warehouse has dropped by 75%, a result of Dodd Frank, the Volcker Rule and Basel III; all demanded more risk capital to be allocated to support corporate debt trading activities. The ratio of corporate debt outstanding to market making capacity has changed from roughly 1:1 in 2006 to 8:1 in 2016. This topic has been widely written about, the trading liquidity in the corporate debt market is extremely thin. Any further selling will disproportionately exaggerate the price declines. The most recent survey by the Federal Reserve revealed that the 22 Primary Dealers (appointed Dealers for Treasury debt issuances) collectively held less than $20 billion of inventories in corporate debt; that is less than 10% of their capacity, a disturbing development.

Macroeconomic Roundup

The slowdown in China and the subsequent end of the commodities super-cycle are probably the most cited headlines. While it might not be easy to comprehend what exactly is happening in China, since official statistics are murky, perhaps one might need to look at the Producer Price Index (PPI) in China. This series tracks the prices of half-finished goods in the middle of the production cycle – rolls of steel, bags of cement and pig iron bars, to name a few. If growth is robust, there will be a shortage of these goods as manufacturers consume more than the suppliers can handle. In China, the reverse is happening. The PPI has been falling for 47 consecutive months, pointing to falling demand/excessive supply, leaving mountains of half-finished goods.

It is well-documented that China is trying to shift from an infrastructure-oriented growth model to a consumer-based economy. However, the shift is a very challenging one. Infrastructure and large government-led projects could be implemented by the state with its centralized leadership, whereas consumer spending growth needs to be driven by the decisions of millions. Essentially, it needs a robust legal framework in which the rule of law can guarantee property rights and facilitate business transactions. This basic framework, however, is lacking in China.

The lack of rule of law is also evident by the numerous industrial accidents that are the result of total disregard for the law and basic safety considerations. It is extremely difficult for a society, as a whole, to provide the comfort needed for entrepreneurs to risk their capital.

China is also hampered by past misallocations of capital, often motivated by corruption, rather than economic needs that soak up otherwise productive financing and the capacity to grow.

These issues cannot be solved by the conventional means of currency devaluations or reductions in interest rates and reserve ratio requirements. China will likely go through a longer and more painful process than most would expect. The bright side is, being authoritarian, it can implement capital and exchange controls effectively and it can freeze the system to limit damage. The Peoples Bank of China has recently unleashed a large amount of liquidity into the system, sending loan creation to soaring levels, in an attempt to prevent a hard landing.

The global economy though, might miss a growth engine for a few years.

Elsewhere, economic data around the world has been mixed.

Business capital spending in the U.S. was in a slump for most of 2015. The latest “ISM U.S. Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ index” fell to 48.2 – being a diffusion index, readings below 50.0 signifies contraction in the manufacturing sector.

One of the few bright spots is the employment report. In January 2016 the unemployment rate fell to 4.9%. The “Average Work Week” increased by 0.1 hour and “Average Hourly Earnings” picked up 0.5%. However, large negative revisions (105,000) to the nonfarm payrolls in November and December took some shine out of the 155,000 gains in January.

U.S. industrial production and capacity utilization both recovered from a string of negative releases, but more positive development is needed to reverse that negative trend of late.

Anemic income growth has been the main reason behind stale Final Demand for the U.S. economy and the key to persistently low inflation. The macroeconomic backdrop should act to cap bond yields/support bond prices. There are other bright spots in the U.S. economy, namely housing and certain areas of technology, but they are not large enough to pull up the rest of the economy. The U.S. is still stuck in a period of slow growth. The good news is that inflation has been very subdued because wage growth is minimal.

Monetary Policy Outlook

Right now, the trend for economic data is on a downward trajectory, and will be until evidence changes. This development will pressure the government bond yield curve lower. Granted that the U.S. Federal Reserve has the intention to raise the Fed funds rate in an interest normalization campaign, soft data will act as a deterrent to further action. Recently, a growing number of Federal Reserve officials have started ‘back peddling’ on rate hike intentions, citing the challenging global conditions and weaker data as reasons.

“Natural Boundaries of Interest Rates”

Given that the macroeconomic backdrop is very favourable for government bonds, the “Natural Boundaries of Interest Rates” should remain stable, with potential to shift lower. In Canada, macroeconomic data are pointing to little or no GDP growth after inflation. The January retail sales report fell 2.2% as it showed declines in all but one category. Autos fell 3.9%. This report brings the Bank of Canada another step closer to the next rate cut. The negative impact from falling energy prices is still being felt as some have long lagging characteristics.

We do not expect the Canadian economy to pick up any time soon. On the inflation front, the lagging characteristics from the oil patch will be disinflationary, as wages decline across the board. At the same time, the falling Canadian Dollar is raising the prices of imports such as fruit and vegetables. These price increases take away discretionary spending power and are a deterrent to economic growth. With commodities prices weak and our exporting machine in serious disrepair, the lower Canadian Dollar will not bring us the corresponding boost in growth either.

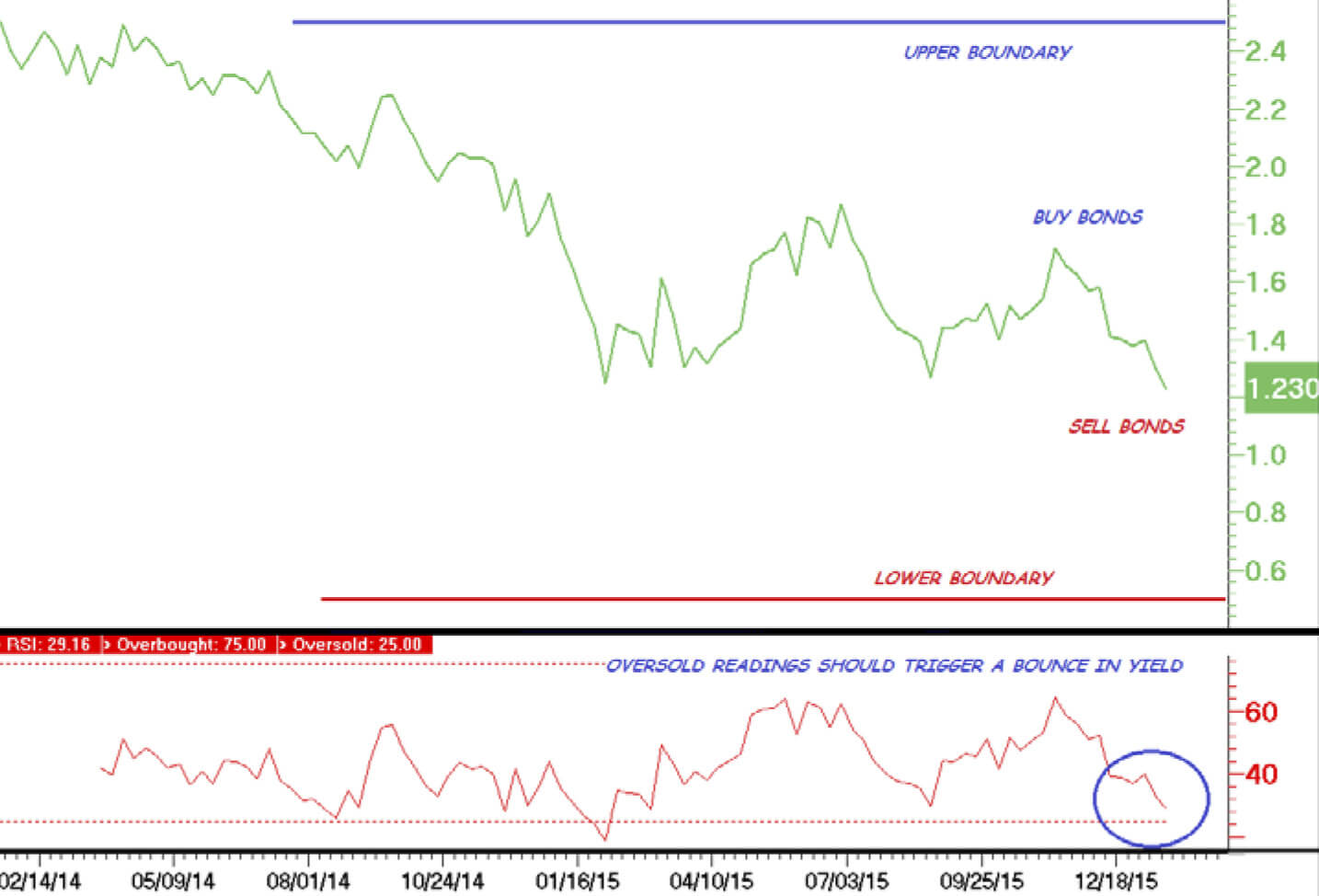

The “Natural Boundaries” of the Government of Canada 10-year bond yield should be 0.50% to 2.5%, given a gross Gross Domestic Product of approximately 1.5%, with potential to shift lower.

Bond Strategy

China, the Emerging Markets, falling commodities prices and tension in the credit markets all combine to provide a favourable backdrop for safe havens like U.S. and Canadian government bonds. Unsavoury data within a challenging macro environment is a recipe for lower bond yields in the longer end of the curve/higher bond prices.

We will be looking for buy signals from technical analysis to accumulate Government of Canada bonds within the context of the “Natural Boundaries of Interest Rates” (chart above) in anticipation of bond yields to fall/bond prices to rise, looking for capital gains when bond yields fall towards the lower boundary by dominant macroeconomic forces.